The Wistar Institute

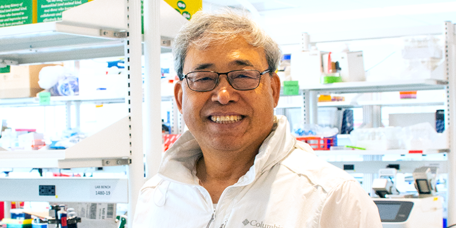

The Wistar Institute Announces the Appointment of Qingsheng Li, Ph.D., to HIV Cure and Viral Diseases Center

The Wistar Institute, a world leader in cancer, immunology, and infectious disease research, announces the appointment of Qingsheng Li, Ph.D., as professor in the HIV Cure and Viral Diseases Center. Li analyzes the complex immune response to HIV pat…

Xiaoyu (Ariel) Zhou, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Vaccine & Immunotherapy Center

Notes from the Field: Dr. Ian Tietjen Returns to Africa, Part Two

Dr. Ian Tietjen is education director, Global Studies & Partnerships, Hubert J.P. Schoemaker Education and Training Center & assistant professor in Wistar’s Vaccine & Immunotherapy Center, where he investigates traditional African medici…

The Wistar Institute, The University of Leeds, and the Perelman School of Medicine Discover New ‘Molecular Glues’ as a Possible Therapeutic Approach for Autoimmune Conditions

PHILADELPHIA — (April 9, 2025) —The Wistar Institute’s Joseph Salvino, Ph.D., — in collaboration with Elton Zeqiraj, Ph.D., of The University of Leeds and Roger Greenberg, M.D., Ph.D., of The Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylv…

Notes from the Field: Dr. Ian Tietjen Returns to Africa, Part One

Dr. Ian Tietjen is education director, Global Studies & Partnerships, Hubert J.P. Schoemaker Education and Training Center & assistant professor in Wistar’s Vaccine & Immunotherapy Center, where he investigates traditional African medici…

Scientists Demonstrate Pre-clinical Proof of Concept for Next-Gen DNA Delivery Technology

PHILADELPHIA — (March 21, 2025) — Scientists in The Wistar Institute lab of David B. Weiner, Ph.D., in collaboration with scientists in the laboratory of Norbert Pardi, Ph.D., at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and at the…

The Wistar Institute Announces Two New Internal Career Development Awards to Support Early Career Scientists

The Wistar Institute has established two new internal funding awards to advance the careers of promising Wistar scientists making an impact in biomedical research.

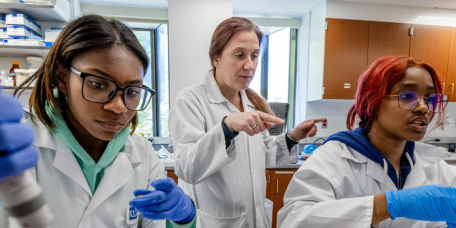

The Wistar Institute’s Commitment to Teaching the Next Generation of Biomedical Researchers

In her role as dean of biomedical studies at The Wistar Institute, Dr. Kristy Shuda McGuire uses her love of science and teaching to nurture future scientists, from high school students to adults.

Wistar Institute Scientists Identify New Strategy to Fight Cancer Caused by Epstein-Barr Virus

PHILADELPHIA — (March 10, 2025) — The Wistar Institute’s Paul M. Lieberman, Ph.D. and lab identified and tested a new method for targeting certain cancers caused by Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), in the paper, “USP7 inhibitors destabilize EBNA1 and suppr…