The Wistar Institute Receives Two Biomedical Research Grants from the V Foundation for Cancer Research

-

CONTACT:

-

Darien Sutton

Grants Fund Projects Aimed at Improving Cancer Therapy

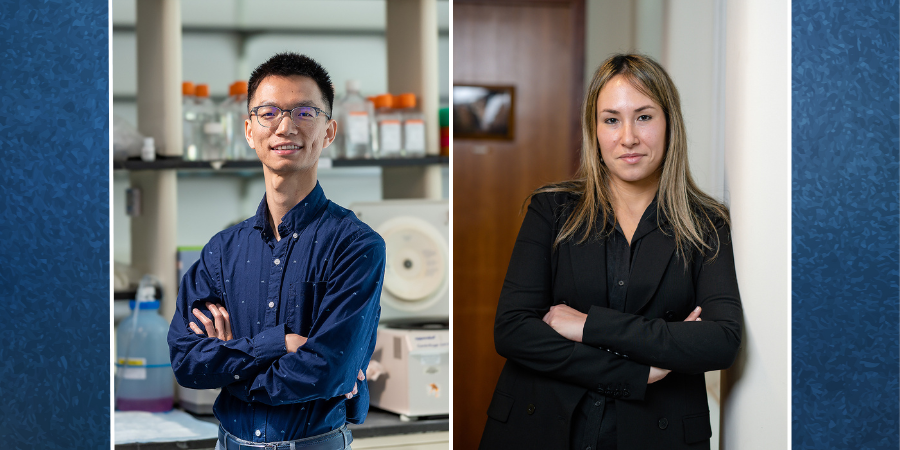

PHILADELPHIA — (December 10, 2024) — The Wistar Institute assistant professors Nan Zhang, Ph.D., and Noam Auslander Ph.D., have both received independent funding totaling $1.2 million over the next three years for cancer research projects from the V Foundation for Cancer Research. The grants are awarded to cancer researchers deemed “V Scholars” and allow Zhang and Auslander to pursue separate projects aimed at new strategies to improve the effectiveness of certain cancer therapies.

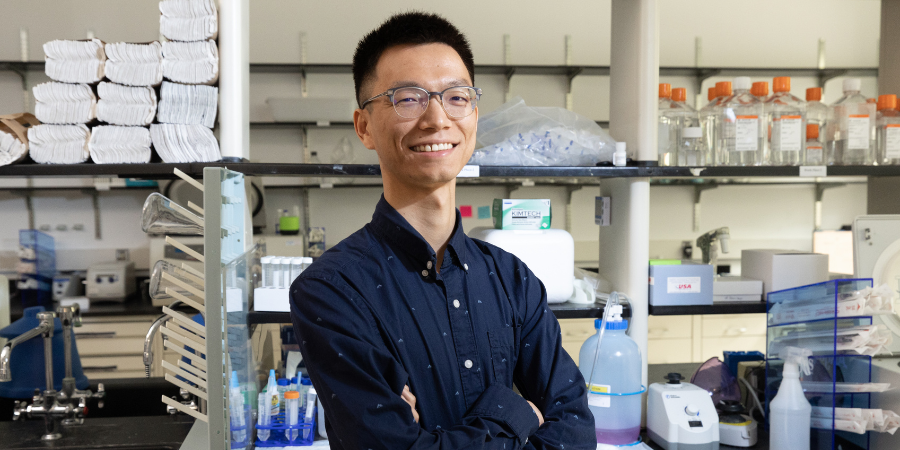

Dr. Nan Zhang recently received a $600,000 V Foundation award, which makes it the second grant Wistar received from the Foundation this year. The funding expands on a promising pilot study that identified a factor that could cause ovarian cancer to resist chemotherapy: a protein called interleukin one beta, or IL1β. This grant is a first step in investigating possible anti-IL1β therapies for chemoresistant ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is one of the most fatal cancers that affect women. While most patients with ovarian cancer respond to chemotherapy at first, the cancer can have potentially fatal consequences if it becomes resistant to treatment.

“This is an exciting opportunity to pursue a promising lead against a notoriously chemoresistant cancer,” said Zhang. “The V Foundation has made this research project possible through their generosity; I look forward to reporting on what we find from our investigation.”

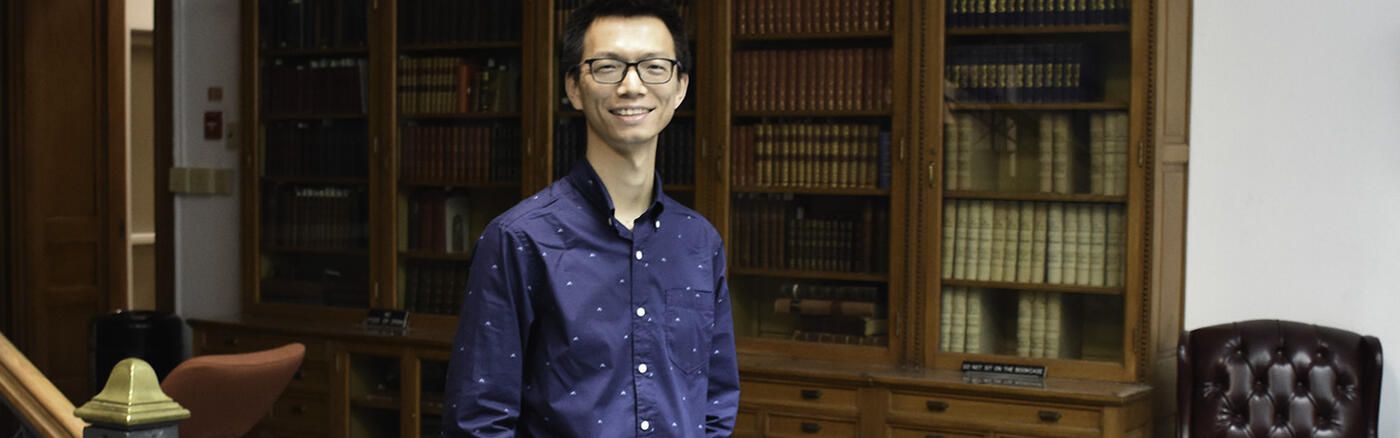

Dr. Noam Auslander was awarded a V Foundation grant earlier this year through the Women Scientists Innovation Award for Cancer Research, and she is an expert in machine learning and computational methods in cancer research. Her $600,000 grant funds a project aimed at improving immunotherapy responses in cancer patients. She and her team want to identify reliable “biomarkers” — accurate indicators of biological states — that could predict the trajectory of a patient’s response to a given immunotherapy treatment. Auslander believes such biomarkers could have the potential to improve clinical decision-making and treatment outcomes by tailoring therapy strategies for individual patients.

“We’re grateful to The V Foundation for the opportunity to launch this important project,” said Auslander. “We know from past experience that large datasets from the microbiome carry important information that can predict health outcomes; with this funding, we hope to find patterns that will predict — and therefore inform — responses to immunotherapy.”

About the V Foundation

The V Foundation for Cancer Research was founded in 1993 by ESPN and the late Jim Valvano, legendary North Carolina State University basketball coach, ESPN commentator and member of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. The V Foundation has funded nearly $400 million in game-changing cancer research grants in North America through a competitive process strictly supervised by a world-class Scientific Advisory Committee. Because the V Foundation has an endowment to cover administrative expenses, 100% of direct donations is awarded to cancer research and programs. The V team is committed to funding the best scientists to accelerate Victory Over Cancer® and save lives.

For a printer-friendly version of this release, please click here.

ABOUT THE WISTAR INSTITUTE:

The Wistar Institute is the nation’s first independent nonprofit institution devoted exclusively to foundational biomedical research and training. Since 1972, the Institute has held National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Cancer Center status. Through a culture and commitment to biomedical collaboration and innovation, Wistar science leads to breakthrough early-stage discoveries and life science sector start-ups. Wistar scientists are dedicated to solving some of the world’s most challenging problems in the field of cancer and immunology, advancing human health through early-stage discovery and training the next generation of biomedical researchers. wistar.org